This policy memo explores some of the questions frequently raised around immigration in the United States and provides facts drawn from publicly available data sets and the academic literature.

Introduction

The Hamilton Project believes it is important to ground the current immigration debate in an objective economic framework based on the best available evidence. In this policy memo, we explore some of the questions frequently raised around immigration in the United States and provide facts drawn from

publicly available data sets and the academic literature.

Most Americans agree that the current U.S. immigration system is flawed. Less clear, however, are the economic facts about immigration—the real effects that new immigrants have on wages, jobs, budgets, and the U.S. economy—facts that are essential to a constructive national debate.

Read the Full Introduction

These facts paint a more nuanced portrait of American immigration than is portrayed in today’s debate. Recent immigrants hail from many more countries than prior immigrants; they carry with them a wide range of skills from new PhDs graduating from American universities to laborers without a high school degree. Most recent immigrants have entered the United States legally, but around 11 million unauthorized immigrants currently live and work in America; the majority of these unauthorized workers settled here more than a decade ago. Each of these immigrant groups affects the U.S. economy in varied ways that should be considered in the current debate around immigration reform.

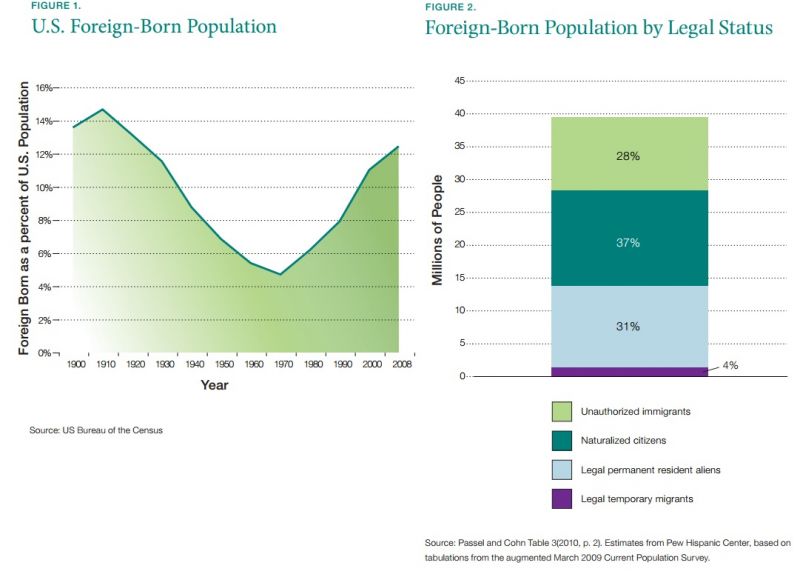

Immigrants now comprise more than 12 percent of the American population, according to recent estimates, approaching levels not seen since the early 20th century. Today’s controversies over immigration echo arguments made a century ago during the last immigration peak. While the demographics of U.S. immigrants have shifted dramatically, the concerns voiced about the social and economic impacts of immigration strike a familiar chord.

A major economic concern is how immigrants influence the wages and employment prospects of U.S. workers. The economic impacts of immigration vary tremendously, depending on whether immigrants are unskilled agricultural laborers, for example, or highly skilled PhD computer scientists. Although their consequences are often conflated, it is constructive to examine the impacts of low-skilled and high-skilled immigrants independently.

Another point of controversy in today’s debate involves the impact of unauthorized immigrants on our economic wellbeing. The best estimates suggest that 28 percent of the total foreign-born population could be unauthorized. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, roughly 60 percent of these unauthorized immigrants are from Mexico. (However, unauthorized immigrants make up only about 21 percent of U.S. residents of Mexican heritage.) When possible, we try to differentiate the figures to more closely understand the different effects—positive or negative—that unauthorized workers may have on the economy.

Of course, there are many factors at play and the economic evidence is only one piece of the puzzle. These facts are designed to provide a common ground that all participants in the policy debate can agree on. In the months and years ahead, The Hamilton Project will return to the issue of immigration as we offer policy recommendations on the economic issues facing the United States.

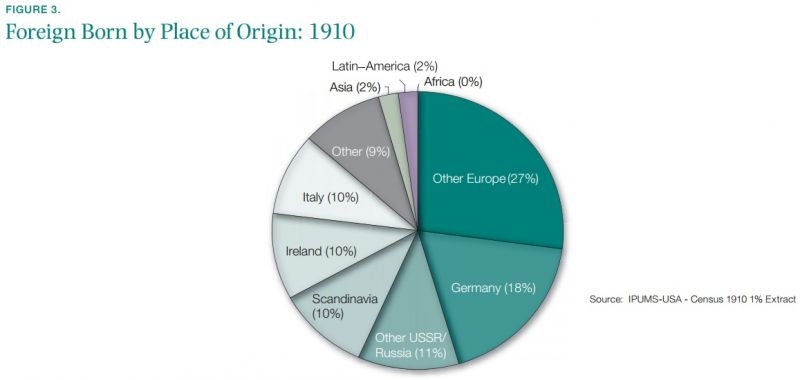

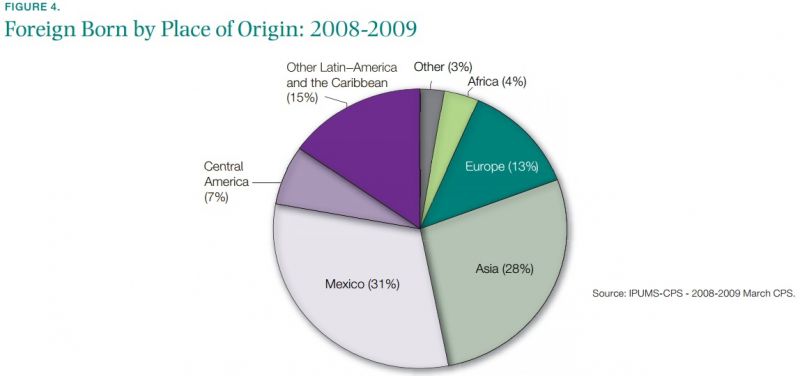

Fact 1: Today’s immigrants hail from more diverse backgrounds than they did a century ago.

America’s immigrants are more diverse than they were a century ago. In 1910, immigrants from Europe and Canada comprised 95 percent of the foreign-born population in the United States. Today’s immigrants hail from a much broader array of countries, including large populations from Latin American and Asia. Not surprisingly, the single largest home country of today’s immigrants is Mexico. All told, immigrants from Latin American and the Caribbean make up 53 percent of the U.S. foreign-born population.

Fact 2: Immigrants bring a diverse set of skills and educational backgrounds.

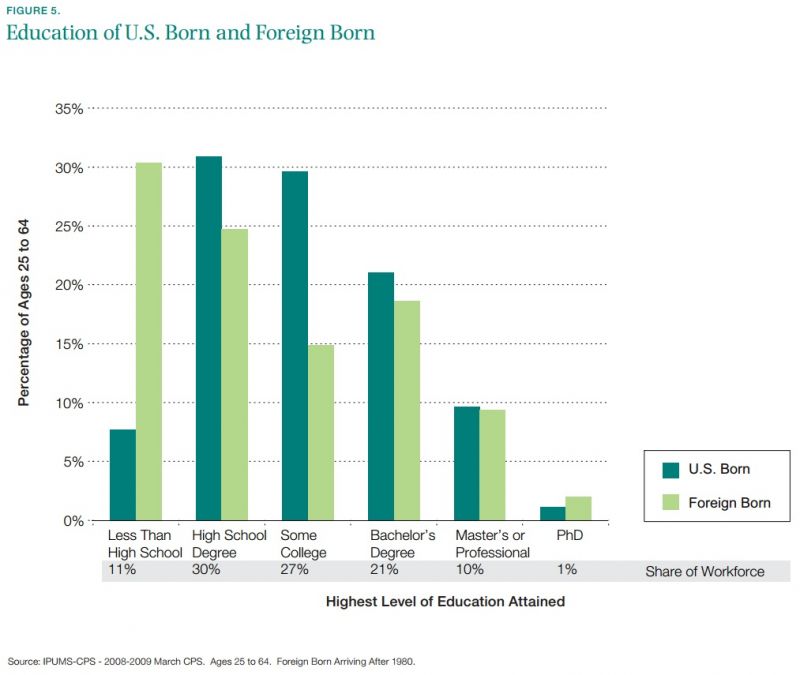

Immigrants are both better and worse educated than U.S.-born citizens. At one end of the spectrum, more than 11 percent of foreign-born workers have advanced degrees—slightly above the fraction of Americans with post-college degrees. Even more striking, more than 1.9 percent of immigrants have PhDs, almost twice the share of U.S.-born citizens with doctorates (1.1 percent).

At the other end of the spectrum, however, immigrants are much more likely than U.S.-born citizens to have less than a high school education. Roughly 30 percent of immigrants lack a high school diploma, nearly four times the figure for U.S.-born citizens.

Fact 3: On average, immigrants improve the living standards of Americans.

The most recent academic research suggests that, on average, immigrants raise the overall standard of living of American workers by boosting wages and lowering prices. One reason is that immigrants and U.S.-born workers generally do not compete for the same jobs; instead many immigrants complement the work of U.S. employees and increase their productivity. For example, low-skill immigrant laborers allow U.S.-born farmers, contractors, or craftsmen to expand agricultural production or to build more homes—thereby expanding employment possibilities and incomes for U.S. workers. Another reason is that businesses adjust to new immigrants by opening stores, restaurants, or production facilities to take advantage of the added supply of workers; more workers translate into more business.

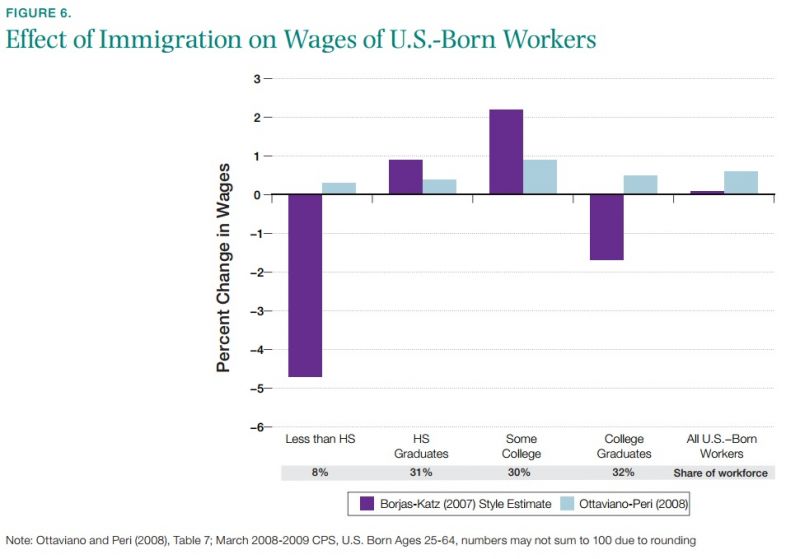

Because of these factors, economists have found that immigrants raise average wages slightly for the United States as a whole. As illustrated in the chart below, estimates from opposite ends of the academic literature arrive at this same conclusion, and point to small but positive wage gains of between 0.1 and 0.6 percent for American workers.

But while immigration improves living standards on average, the economic literature is divided about whether immigration reduces wages for some groups of American workers. In particular, some estimates suggest that immigration has reduced the wages of low-skilled workers and college graduates. This research, exemplified by the purple bars in the chart below, implies that immigrant workers may have lowered the wages of low-skilled workers by 4.7 percent and college graduates by 1.7 percent. However, other estimates that examine immigration within a different economic framework (the light blue bars in the chart) find that immigration raises the wages of all U.S. workers—regardless of their level of education.

Immigrants also affect the well-being of U.S. workers by affecting the prices of the goods and services that they purchase. Recent research suggests that immigrant workers enhance the purchasing power of Americans by lowering prices of “immigrant-intensive” services like child care, gardening, and cleaning services. By making these services more affordable and more widely available, immigrant workers benefit U.S. consumers who purchase these services.

Fact 4: Immigrants are not a net drain on the federal government.

Taxes paid by immigrants and their children—both legal and unauthorized—exceed the costs of the services they use. In fact, a 2007 cost estimate by the Congressional Budget Office found that a path to legalization for unauthorized immigrants would increase federal revenues by $48 billion but would only incur $23 billion of increased costs from public services, producing a surplus of $25 billion for government coffers. According to the Social Security Administration Trustees’ report, increases in immigration have also improved Social Security’s finances.

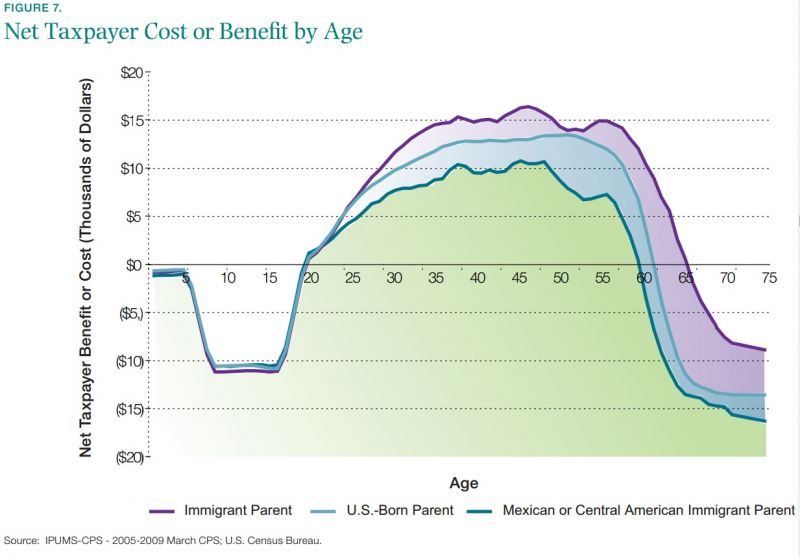

Many government expenses related to immigrants are associated with their children. From a budgetary perspective, however, the children of immigrants are just like other American children. The chart below compares the taxes paid and expenditures consumed by the children of immigrants and by the children of U.S.-born citizens over their lifetimes. Both the immigrant children and children of U.S.-born citizens are expensive when they are young because of the costs of investing in children’s education and health. Those expenses, however, are paid back through taxes received over a lifetime of work. The consensus of the economics literature is that the taxes paid by immigrants and their descendants exceed the benefits they receive—that on balance they are a net positive for the federal budget.

However, it is important to recognize that some of these budgetary costs are unequally shared across state and local governments. Education and health services for immigrant children are generally state liabilities and are concentrated in immigrant-heavy states like California, Nevada, Texas, Florida, New Mexico, and Arizona. While the federal government is a winner in terms of tax revenues, these states may be burdened with costs that will only be recouped over a number of years, or, if children move elsewhere within the United States, may never fully be recovered.

Fact 5: Both immigration enforcement funding and the number of unauthorized immigrants have increased since 2003.

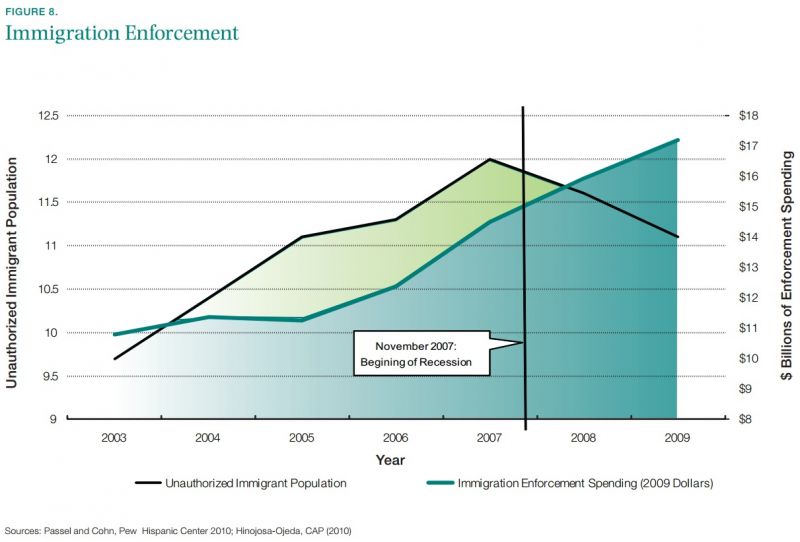

The United States has dramatically raised immigration border security and enforcement funding to $17 billion over the past decade in an effort to improve national security, as well as to stem the flow of unauthorized immigrants entering the country. A secure border is required for national security and to enforce legal and customs requirements. As a tool of immigration policy, however, the available evidence suggests that this increased spending is unlikely to have had a major effect on the number of unauthorized immigrants living in the United States. Indeed, the number of unauthorized immigrants continued to rise between 2003 and 2007. The decrease in unauthorized immigration since 2007 is likely due to the Great Recession.

One reason that increases in border patrol have had modest impacts on the number of unauthorized immigrants is that most arrived before the enhanced security measures were implemented after 2001; according to estimates from the Pew Hispanic Center, more than half of unauthorized immigrants arrived here before 2000. In addition, some research suggests that increased security has resulted in unauthorized immigrants staying in the United States longer rather than risking detection by visiting home.

Fact 6: Immigrant do not disproportionately burden U.S. correctional facilities and institutions.

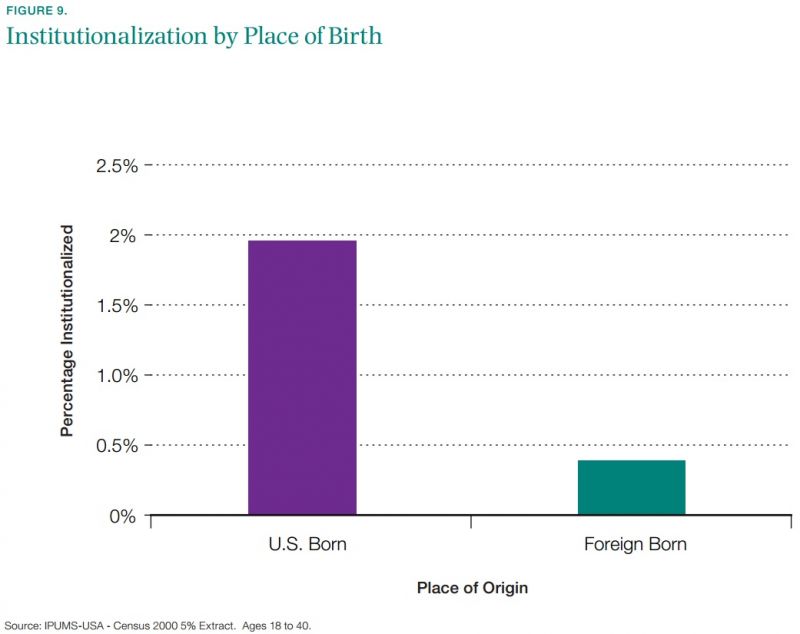

Immigrants are institutionalized at substantially lower rates than U.S.-born citizens. Looking at Census data covering correctional facilities and mental hospitals, U.S.-born citizens are more than five times more likely than immigrants to be institutionalized. (One study estimated that as many as 70 percent of the institutionalized population are housed in correctional facilities). This evidence suggests that immigrants impose fewer costs on taxpayers from crime and institutionalization than do U.S.-born citizens.

Fact 7: Recent immigrants reflect America’s melting pot.

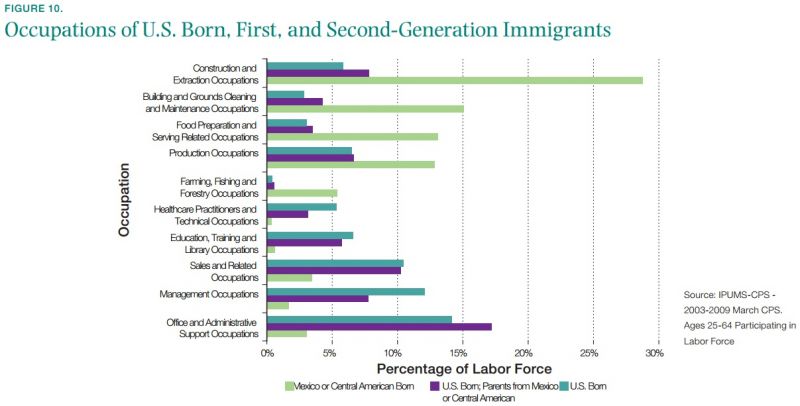

Some groups are concerned that recent immigrants choose not to integrate and assimilate into American social and economic life, in contrast to previous generations of immigrants. The data suggest this is not true. Recent waves of immigrants and their children are integrating into the U.S. economy, just as previous immigrant families did. This is true also for immigrants from Mexico and Central America, where firstgeneration immigrants have tended to concentrate in sectors like construction, food preparation, and agriculture. As seenin the chart below, the children of these immigrants engage in occupations more closely resembling those of U.S.-born citizens than the occupations of their parents.

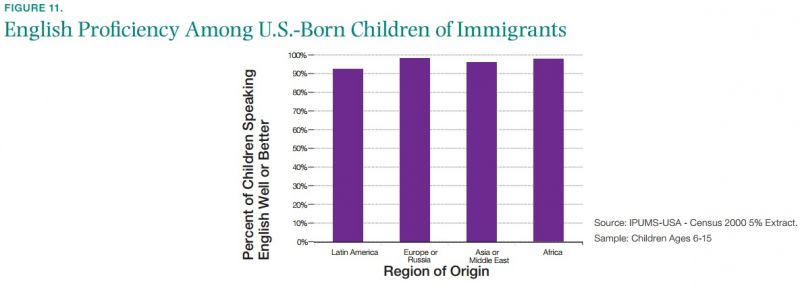

Not only do immigrants assimilate into U.S. economic life, but they also integrate in other ways. In addition to being vital to gaining employment, speaking English is a measure of social assimilation into the United States. More than 90 percent of the children of recent immigrants speak English, regardless of their country of origin, according to the U.S. Census.

Fact 8: The skill composition of U.S. immigrants differ from that of other countries.

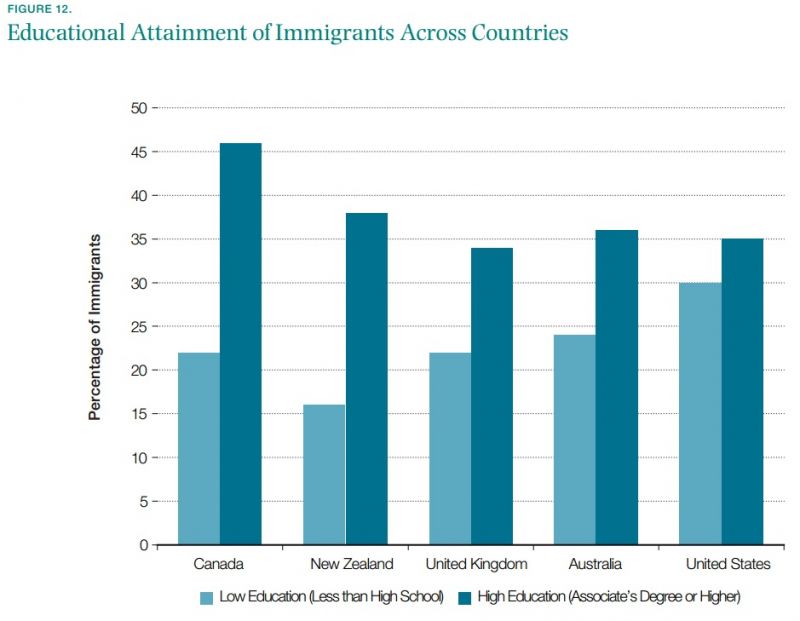

Compared to countries like Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, the United States has a greater proportion of lowskilled immigrants. About 30 percent of immigrants in the United States possess a low level of education and only 35 percent possess a high level of education. In Canada, only 22 percent have a low level of education (equivalent to less than high school in the United States) while more than 46 percent have a high level of education (roughly equivalent to an associate’s degree or higher in the United States).

Countries like Canada attract a greater influx of immigrants with higher education levels and specialized skills through immigration policies that specifically favor visa applicants with advanced degrees or work experience. The composition of U.S. immigrants is the result of our immigration policies, which place more emphasis on family relationships and less consideration on skill or education than many other countries when granting permanent residence.

Fact 9: Immigrants start new businesses and file patents at higher rates than U.S.-born citizens.

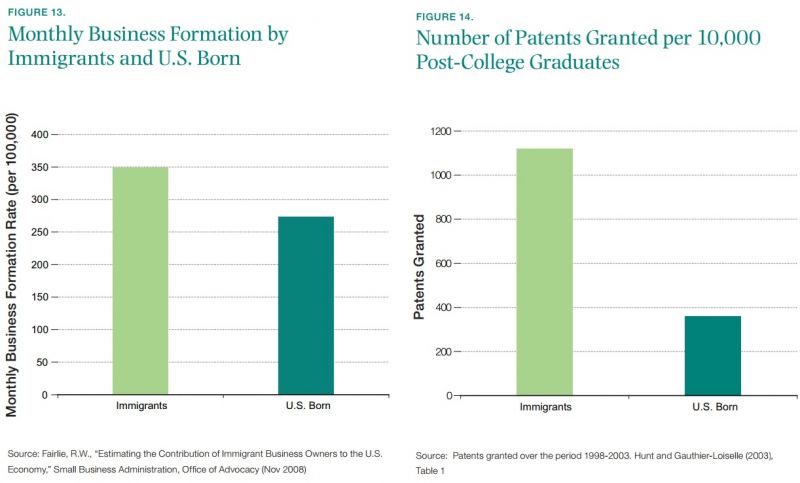

Today’s immigrants possess a strong entrepreneurial spirit. In fact, immigrants are 30 percent more likely to form new businesses than U.S.-born citizens. Furthermore, evidence shows that foreign-born university graduates are important contributors to U.S. innovation—among people with advanced degrees, immigrants are three times more likely to file patents than U.S.-born citizens. Such investments in new businesses and in research may provide spillover benefits to U.S.-born workers by enhancing job creation and by increasing innovation among their U.S.-born peers.

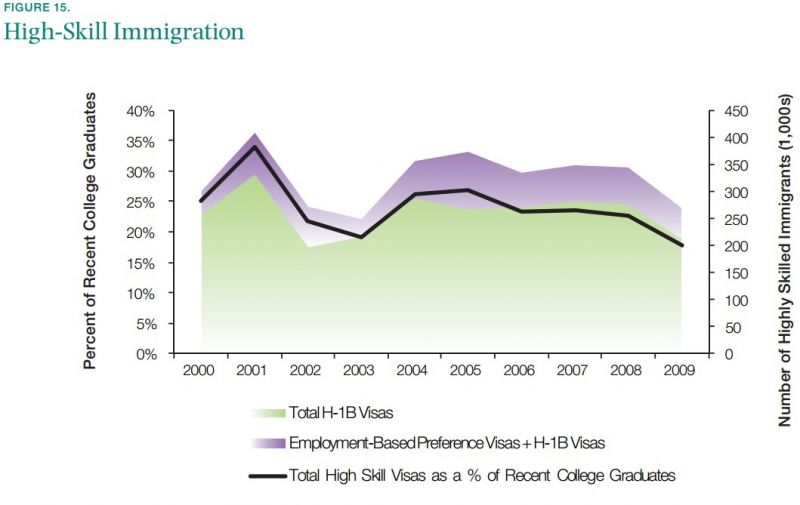

Fact 10: America is issuing a declining number of Visas for high-skill workers.

With its top-level universities, dynamic business environment, and wide-ranging economic opportunities, the United States has a history of attracting high-skill workers. However, a recent study suggests that this trend may be waning; many of today’s international students either plan to leave the United States or are uncertain about remaining, raising the potential for a reverse brain‐drain of the skilled workers who contribute to U.S. global competitiveness. As seen in the graph below, the number of high-skill visas has also declined somewhat since 2000. In 2009, 270,326 visas for high-skill workers were available, down from 301,328 in 2000.