This proposal is chapter one of The Hamilton Project’s Policies to Address Poverty in America, and a segment in Promoting Early Childhood Development.

Introduction

Poverty has little association with the cognitive abilities of nine-month-old children (Fryer and Levitt 2013). By the start of kindergarten, however, not only do poor children perform significantly worse on tests of cognitive ability than children from higher-income families, but teachers also report that these children have much more difficulty paying attention and exhibit more behavioral problems (Duncan and Magnuson 2011). The poverty gap in school readiness appears to be growing as income inequality widens (Reardon 2011).

The Policy Landscape

One popular proposal to narrow this gap is to expand formal educational opportunities to poor children under the age of five. Stark gaps in preschool participation by family socioeconomic status mirror the achievement gaps described above. The most recent data available show that only about 50 percent of four-year-old children in families in the lowest income quintile are enrolled in preschool. Among families in the top income quintile, on the other hand, the preschool enrollment rate of four-year-olds is considerably higher, at 76 percent. Nearly all (88 percent) of preschool participants in the lowest-income families are enrolled in public programs.

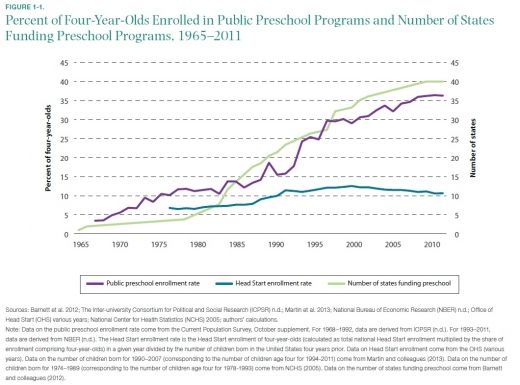

Poor children can currently attend preschool for free through two programs: the federally funded Head Start program, which targets children in families with incomes less than 130 percent of the federal poverty level; and state-funded public programs, which may also serve middle-class children. As shown in figure 1-1, only about 10 percent of four-year-old children nationwide participate in Head Start, a rate that has stayed roughly constant for the past twenty years. Essentially all the growth in public preschool enrollment over time has come from the expansion of state-funded programs, which grew from four states in 1980 to forty states today.

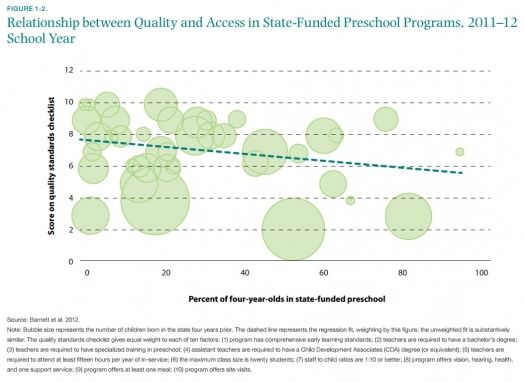

Even so, many state programs have weak standards, as shown in figure 1-2. During the 2011–12 school year, only 9 percent of all four- year-olds nationwide—roughly 31 percent of those enrolled in state-funded preschools—were enrolled in programs that met at least eight common quality benchmarks related to curriculum, teacher education, class size, and support services. The average Head Start program meets only five of these benchmarks (Espinosa 2002).

In this context, President Obama proposed to expand access to preschool education while simultaneously leveling up preschool quality nationwide (Office of the Press Secretary 2013). The White House proposal would provide block grants to states to offer free preschool education to four-year-old children from low- and moderate-income families, provided that these preschool programs score highly on the quality standards checklist presented on the vertical axis in figure 1-2. State and local governments are not waiting for federal action. Most notably, New York City mayor Bill DeBlasio campaigned on the promise of funding universal pre-kindergarten (pre-K), and in March 2014 New York governor Andrew Cuomo and the state legislature agreed to a five-year, $1.5 billion plan to offer high-quality full-day pre-K—not just in New York City, but across the state.

Evidence on the impacts of early education is broadly supportive of policy efforts in early education. The research on early education has shown it improves participants’ outcomes across a variety of dimensions: higher school attendance rates, fewer failing grades, less grade retention, a higher likelihood of graduating from high school, and less involvement in criminal activity. Improvements in these areas account for many of the economic benefits of preschool programs. However, important questions remain regarding access— he benefits versus the costs of expanding public preschool options beyond lower-income children—and exactly how quality would be best defined from a policy perspective. This policy memo is directed primarily toward state and local policymakers who want to strengthen the public preschool options in their area while considering budgetary trade-offs.