Activity in the labor market picked up slightly last month, according to today’s employment report. Payroll employment increased by just over 100,000 jobs in September, an increase that partially reflected the return to work of striking telecommunications workers. The unemployment rate was unchanged at 9.1 percent. Since April, payroll employment has increased by an average of 72,000 per month, compared with an average of 161,000 for the prior seven months.

In previous postings, The Hamilton Project has explored the earnings of both men and women. For men, we found that earnings have been on the decline because of stagnant wages for those who work and declining employment rates. For women, earnings have increased as more women joined the labor force, entered higher-paying professions, and gained higher levels of education—all of which enable them to command higher salaries. We have also investigated the earnings of the typical American family with kids and explained how families are earning more, but only because they are working more.

We focus this month on the family earnings devoted to the typical American child and how those earnings have evolved over the past 35 years. Our key finding is that there is a growing opportunity gap between children who are better off and those who are worse off, which is likely to lead to a more challenging future for many of today’s youth. As in previous months, the Hamilton Project also continues to explore the “job gap,” or the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while also absorbing the roughly 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

Family Earnings of the Median Child

How we are raised and the resources available to us as children have long-term effects on our quality of life. There is mounting evidence to suggest that our parents’ education levels and employment situations have implications that extend far into adulthood. For example, research has shown that children with a parent who suffered a job loss as a result of a business closure are more likely to be unemployed and receive social assistance later in life and less likely to complete high school and attend college; these effects may be most severe for children whose parents’ income is already below the poverty line (Oreopoulos et al. 2008; Page et al. 2007). What is more, evidence suggests that family background and community influences may be more important determinants of the future earnings and opportunities of children today than it was in the 1970s (Mazumder and Levine 2004).

Annual family earnings provide one important measure of the resources available to children. This measure takes into consideration the labor market opportunities and earnings of parents and whether the child is living with one or both parents. After adjustment for inflation, the family earnings of the median child have been more or less flat since 1975, with some fluctuation with the business cycle—most notably a recent dip resulting from the Great Recession. The median child in 2010 lived in a family that earned approximately $45,750 per year, down nearly 14 percent from 2006 and 7 percent from 1975. When we adjust family earnings for changes in family size (families are smaller today than they were thirty years ago), we find the median child is no better off today in terms of family earnings than she was in 1975.

One reason that the median child has made little progress over the last 35 years is that more and more kids are being raised in single-parent households. In 1968, 12 percent of all children lived in single parent families, while today about 3 in 10 are in single parent or unmarried families. Therefore even though the earnings of the typical two-parent family have increased over time, those gains have been offset because fewer children benefit from the earnings of both parents.

The Widening Opportunity Gap

The fact that the typical American child is living in a family where resources have not increased in 35 years is alarming. Of greater concern is the fact that the stasis in the family earnings of the median child masks an increasing gap between children whose parents are at different ends of the earnings distribution.

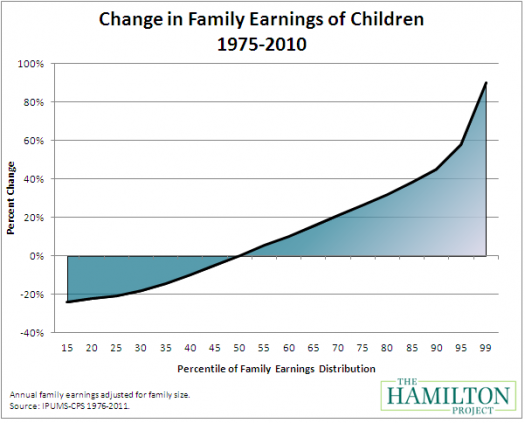

While the median child has been barely treading water for the last three decades, some children are doing much better and others much worse. In a nutshell, half of the children in the United States have experienced gains in their family earnings, with the most well-off enjoying a disproportionate share of those gains. However, the other half of America’s children are worse-off than their counterparts 35 years ago.

Children at the 90th percentile of the distribution of family earnings experienced a 45 percent increase in their family earnings over the last 35 years. At the same time, children at the 25th percentile of the distribution have seen real declines in family earnings of over 20 percent. These trends are shown in the chart below:

Part of this widening divide has to do with changes in the labor market that have disproportionately rewarded parents with higher levels of education. In 2010, the family earnings of the median child in a family with at least one college-educated parent were about $92,000 per year, 14 percent higher than in 1975. At the same time, children living in families without a parent who had more than a high school diploma (including either single parent or married parent families) have seen their family earnings decline by 51 percent over the same period. Although the share of children living in a family with at least one college-educated parent has increased steadily over this time period, most children still do not enjoy this advantage: in 2010, just 36 percent of children lived with at least one parent who had a college degree.

What are the implications of this for America’s children? It is clear that what we are exposed to in childhood can have lifelong impacts. If there is a widening gap between the “haves” and the “have nots” starting at a young age, this may lead to persistent differences in the opportunities available to children, and threaten the intergenerational mobility that is at the heart of the American dream.

The September Jobs Gap

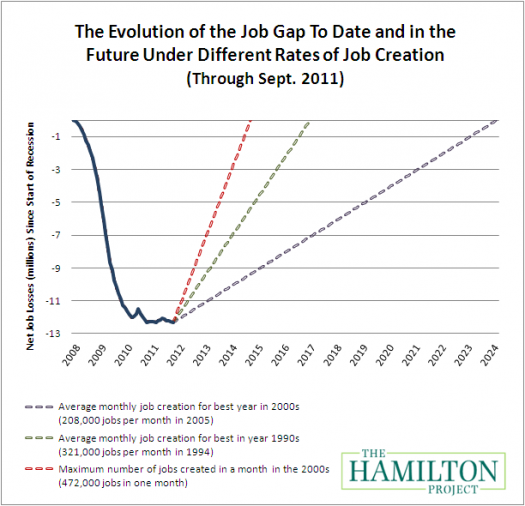

This analysis has shown that American families continue their struggle in the aftermath of the Great Recession. As of September, our nation continues to face a “job gap” of 12.3 million jobs, down by 77,000 jobs from August.

The chart below shows how the job gap has evolved since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, and how long it will take to close under different assumptions for job growth. The solid line shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began. The broken lines track how long it will take to close the job gap under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward.

If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until February 2024—about 12 and a half years—to close the job gap. Given a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by December 2016—not for another five years.

Conclusion

As American workers continue to find their footing in today’s global economy it is important to focus on the well-being of our nation’s children. A widening gap between the family earnings of better- and worse-off children is indeed alarming, highlighting the differences in opportunities available for today’s youth.

These findings also reinforce the importance of a sound education. The evidence is clear that family incomes are linked heavily to the educational attainment of the parents.

Parents with college degrees earn more and are more likely to be employed in both good times and bad. Research suggests that these differences in parental outcomes can have enormous consequences for their children, and that opportunities available to us growing up are indeed linked to opportunities later in life.

In late September, The Hamilton Project released three new policy proposals for improving student achievement in K-12 education. On November 30th we will host a conference that will focus on training proposals to help America’s disadvantaged and dislocated workers get back to work. By improving America’s education system and putting better training systems in place, we have the potential to impact the lives of working-adults, and those who depend on them.