Each March, we celebrate International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month. This is an opportune moment to reflect on women’s changing labor market fortunes and what they mean for the country.

Trends in Women’s Labor Force Participation

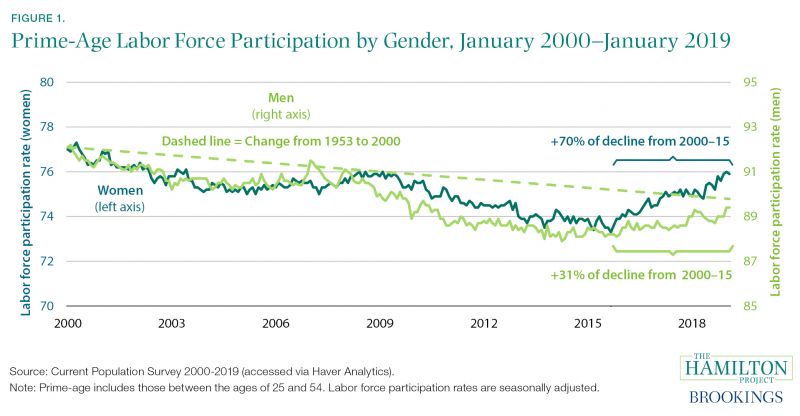

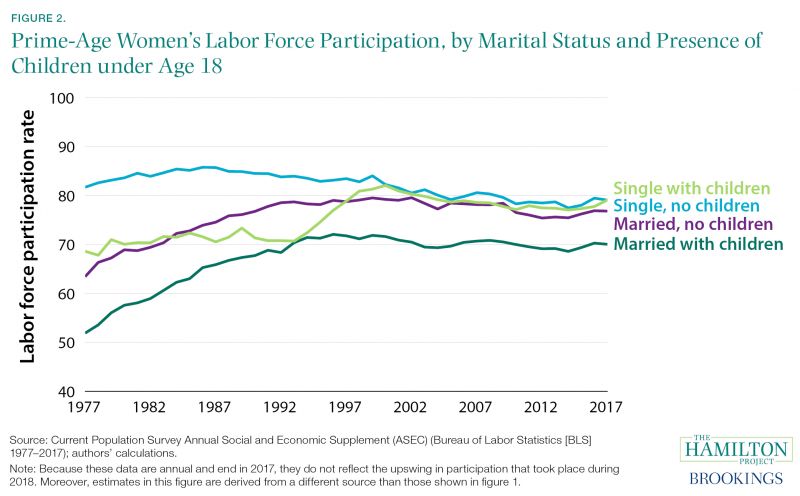

From the early 1960s through 2000, the overall U.S. labor force participation rate grew from under 59 percent to just above 67 percent. This increase was driven by the entrance of millions of women into the labor force: where only 38.3 percent of women participated in 1963, 59.9 percent were employed or searching for employment in 2000. Women from all walks of life—differing by age, race and ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, and parental status—participate at higher rates than they did in the 1960s. This transformation of American life was the cause and effect of dramatic shifts in the economic and social possibilities available to women. At the macroeconomic level, one core consequence was a massive increase in family incomes and economic output. These improvements were all the more welcome in an economy characterized by sluggish wage growth for low-income households and declining male employment: prime-age (i.e., 25- to 54-year-old) men participated at a 96.8 percent rate in 1963 and 91.6 percent in 2000. Since 2000, the participation of prime-age men continued to deteriorate at roughly the same trend as it had for 50 years, falling to 89.0 percent in 2018. But the turn of the new millennium marked two important shifts that shaped overall U.S. labor force participation. The population began to age quickly; 27.1 percent of Americans were 55 or older in 2000, rising to 36.2 percent in 2018. The second shift was in the participation rate of prime-age women, which reversed its steady rise and declined from 76.7 percent in 2000 to 73.7 percent in 2015. In fact, in the first 15 years of the 21st century, it appeared that prime-age women in the United States were starting to mirror prime age men in their declining labor force participation (see figure 1). In stark contrast, prime-age women’s labor force participation in countries like Japan and France caught up to and exceeded U.S. women’s participation. But much like 2000 is now recognized as a pivotal year for the U.S. labor market, 2015 is beginning to look like another turning point. In part due to the ongoing strengthening of the labor market, both prime-age women’s labor force participation and prime-age men’s participation have increased sharply from 2015 through the beginning of 2019. Figure 1 shows that prime-age women now participate at higher levels than prior to the Great Recession and have now made up 70 percent of their January 2000–September 2015 decline, while prime-age men have only made up 31 percent over the same period and are still below 2007 levels.  Changes in prime-age women’s labor force participation rates over the decades have been led at different times by single and married women, and by women with and without children, as shown in figure 2. From 1977 through 1993, rising women’s participation was driven by married women. But from 1993 to 2000, single women with children experienced more than an 11-percentage-point rise in participation—essentially catching up with childless single women—while trends for other women flattened out. Public policies like welfare reform and expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit played important roles, as did the tight labor market of the late 1990s. From 2000 to 2015, women of all four groups were less likely to be in the labor force, and since 2015 all four groups have regained ground. The recent rebound seems to be driven less by a single policy or cultural shift affecting one group of women. Still, the difference between women and men’s participation changes in the last three years suggests that women’s improving participation rate is due to more than just the recovering labor market. Continuing cultural and institutional shifts are bringing women into the labor market, and as international evidence suggests, there is room for considerably more growth.

Changes in prime-age women’s labor force participation rates over the decades have been led at different times by single and married women, and by women with and without children, as shown in figure 2. From 1977 through 1993, rising women’s participation was driven by married women. But from 1993 to 2000, single women with children experienced more than an 11-percentage-point rise in participation—essentially catching up with childless single women—while trends for other women flattened out. Public policies like welfare reform and expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit played important roles, as did the tight labor market of the late 1990s. From 2000 to 2015, women of all four groups were less likely to be in the labor force, and since 2015 all four groups have regained ground. The recent rebound seems to be driven less by a single policy or cultural shift affecting one group of women. Still, the difference between women and men’s participation changes in the last three years suggests that women’s improving participation rate is due to more than just the recovering labor market. Continuing cultural and institutional shifts are bringing women into the labor market, and as international evidence suggests, there is room for considerably more growth.

Barriers Remain

Despite the recent increase in labor force participation and decades-long progress in the labor market, women still face daunting barriers in the workforce. More than half of prime-age women outside the labor force list caregiving as their reason for nonparticipation. While many of these women do not desire paid work, others would take employment if child care was easier to obtain or if employment and child care were easier to balance. For many of those women who do have paid employment, occupational segregation and earnings gaps with male counterparts are a continuing problem. These are challenges not just for individual women, but also for the country as a whole. Without fully applying the talents of half the population, the U.S. economy will not operate at its full potential or spread the benefits of economic growth to all families. Policymakers should carefully consider evidence-based remedies that can remove the obstacles women face in accessing labor market opportunities.