In this piece, we analyze how changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; formerly the Food Stamp Program) that are now law due to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) will affect the program’s response to recessions. At a time of significant uncertainty about the direction of the economy, OBBBA makes structural changes to SNAP that we find will result in the program being substantially and detrimentally less responsive to deteriorating or poor economic conditions. Unless OBBBA’s SNAP cuts are reversed, those cuts will greatly diminish or end SNAP’s critical role as a national automatic stabilizer.

Economic recessions result in widespread pain: an increased likelihood of job loss, longer unemployment spells, less access to credit, financial stress, business closures, reduced tax revenues, and lower economic growth. Not all economic downturns are nationwide; they can be local or regional due to factors such as the decline of a regional economic sector, plant closures, or natural disasters. When there is a recession, policymakers can employ a range of fiscal and monetary policy tools to address hardship and temper the depth and duration of the downturn; but, it takes time to recognize that a recession has started, then it takes time to put together and pass pertinent legislation or adjust monetary policy, and then it takes time for resources to hit the ground.

As economic conditions deteriorate, some policies—often referred to as automatic stabilizers—do not require any policymaker action at all to kick in. Historically, SNAP has been a key automatic stabilizer because when people lose their jobs or experience a decline in income and become newly eligible for SNAP, they can enroll in the program and quickly receive and spend benefits at grocery stores. SNAP not only helps to provide a basic need, resources to put food on the table, but because recipients spend the benefits immediately in their local communities, the program also helps stabilize and stimulate the economy. These dynamics are temporary: As economic conditions improve and need dissipates, SNAP enrollment and attendant spending declines.

The policy change under OBBBA that will most severely undercut SNAP’s role in fighting recessions is the transfer, for the first time, of significant program costs from the federal government onto states. We expect that changing the structure of SNAP by ending guaranteed full federal funding of program benefits, as OBBBA does, will almost certainly lead some states to cut SNAP participation substantially and is likely to lead other states to end their participation in the program entirely. This post-OBBBA dynamic will worsen as economic conditions deteriorate: Nearly all states must balance their budgets even in recessions, when their revenues are declining, and will feel pressures to cut SNAP. As a result, instead of expanding during recessions in tandem with the economy’s contraction, SNAP is likely to contract, too, causing the economy to weaken still further.

OBBBA also changes SNAP work requirement policy, undermining SNAP’s role both in providing support for workers who lose their jobs and in stimulating local economies experiencing job loss during economic downturns. Older Americans between the ages of 55 and 64 and parents without children under age 14, both without a proven work-limiting disability, will be newly subject to time limit work requirements alongside people between the ages of 18 and 54 without dependents or a proven work-limiting disability. OBBBA ended exemptions from time limit work requirements for veterans, those experiencing homelessness, and former foster care youth.

Additionally, OBBBA severely curtails states’ ability to request waivers from time limit work requirements when local economies are struggling by limiting waivers to areas with unemployment rates of at least 10 percent, an employment level well above that experienced in many parts of the country even in deep recessions. USDA will terminate all existing waivers on November 2, 2025. Conditioning SNAP eligibility on work when the economy contracts and/or labor market conditions are poor will penalize workers who have recently lost their jobs or income, making it harder for them to get back on their feet and back to work.

The Hamilton Project has produced extensive research on countercyclical policy and commissioned dozens of policy proposals about how to best combat recessions, including the volumes Recession Ready and Recession Remedies. Delivering timely, targeted, and temporary resources to those most in need and most likely to spend those resources quickly through automatic stabilizer programs like SNAP is critical to making a recession more shallow and shorter. Policymakers could pursue a different course, reforming SNAP to be even more effective, both in general and in responding to recessions.

For example, we have proposed that a temporary increase in federally funded SNAP benefits should automatically kick in when the economy contracts, as should a nationwide suspension of SNAP work requirements. Such policies, which are similar to those Congress enacted during the last two recessions, would protect Americans from some of the hardship that comes with a recession, break the relationship between work and program eligibility when there are many fewer jobs available, and stimulate the economy during recessions by targeting resources that will be spent quickly to those in need. However, these countercyclical SNAP policies, as well as Congress’ response during the Great Recession and the COVID-19 recession, reflect SNAP prior to OBBBA.

The best policy response to the SNAP changes in OBBBA is for Congress to undo the SNAP changes in OBBBA.

Short of that, Congress should prioritize annulling the structural change that pushes a portion of SNAP benefit costs onto states before it takes effect. Congress and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) should also consider reinstating the prior criteria for SNAP work requirements and waivers of those requirements, or at a minimum, reconciling SNAP work requirement waiver rules with the new Medicaid work requirement waiver rules in OBBBA, as they differ in important ways without any justification being provided for the divergence (other than the need for the congressional committees that wrote OBBBA to meet steep, pre-set spending-cut targets). In addition, while we believe that the evidence supports ending SNAP time limit work requirements in policy and practice, Congress should at least repeat past precedent by suspending time limit work requirements nationwide when there is a recession.

An unprecedented mandate for states to pay for a portion of SNAP benefits will end SNAP in some states and inhibit SNAP’s ability to respond to recessions

For the entirety of its more than 50-year history, SNAP benefits have always been paid in full by the federal government. Starting in October 2027, OBBBA ends this guarantee of full federal funding of SNAP benefits by tying the share of benefits that a state will have to pay for to the state’s SNAP payment error rate (PER). Shifting a portion of SNAP benefits onto states is unprecedented and will occur on top of other parts of OBBBA, including its extensive Medicaid cuts, that also shift substantial new costs onto states.

In providing an estimate for the effect of pushing a substantial share of SNAP benefit costs onto states, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has concluded that this policy will lead some states to drop out of the program entirely; we agree. States could also take steps to limit enrollment, make significant cuts elsewhere in their budget to make room for more state spending on SNAP, or raise taxes or revenue by other means to be able to afford to remain in the program. Uncertainty year-to-year around the state’s PER and program enrollment will make it quite difficult for states to plan and budget.

What is the new OBBBA policy?

The SNAP payment error rate (PER) reflects how accurately states make eligibility and benefit determinations for participating households, although wrongly rejecting an eligible applicant is not considered an error. The PER is also not a measure of fraud. Prior to the passage of OBBBA, when a state has had a PER of 6 percent or more, the state would work with USDA on a Corrective Action Plan, with substantial penalties levied against states with persistently high PERs.

Starting in FY2028 (October 1, 2027), OBBBA requires states to pay a portion of SNAP benefits based on the state’s FY2025 or FY2026 error rate. Starting in FY2029 and going forward, states’ payment rates will be based on the PER from three years prior. Table 1 summarizes the relationship between PERs and the share of SNAP benefits that a state will have to pay, from nothing if a state’s PER is less than 6 percent for a given year to 15 percent of benefits. Since 2003, only South Dakota has never had PER above 6 percent.

OBBBA includes a temporary delay in the state payment requirement for states with error rates above 13.32 percent. These states will be exempt from the requirement to pay for any portion of SNAP benefits for up to two additional years. Specifically, if in FY2025 a state has a PER above 13.32 percent, it is exempt from paying any portion of SNAP benefits until FY2029; if its FY2026 PER is above 13.32 percent, it is exempt until FY2030. Thus, if a state’s PER stays above 13.32 percent for the next two years, the state pays no portion of SNAP benefits for up to two years, but if a state’s error rate falls from above 13.32 to between 6 and 13.32 percent, that will trigger a requirement for the state to pay between 5 and 15 percent of benefit costs.

At the same time that the law ties strong incentives to reducing PERs, OBBBA also makes it harder for states to invest the resources needed to reduce errors by cutting the share of state SNAP administrative costs that the federal government covers in half (from 50 percent to 25 percent) starting in FY2027. Furthermore, eliminating certain benefit determination simplifications and expanding work requirements, as OBBBA does, will make SNAP eligibility and benefit determinations more complex. Greater complexity tends to result in more errors.

What are states’ payment error rates?

Figure 1 is a map that shows the payment error rate (PER) for each state for the most recent year of data, FY2024. Only eight states had a PER below 6 percent. Six states had a PER between 6 and 7.9 percent, 16 states had a PER between 8 and 9.9 percent, and 11 states had a PER between 10 and 13.32 percent. Nine states and D.C. had an error rate above 13.32 percent.

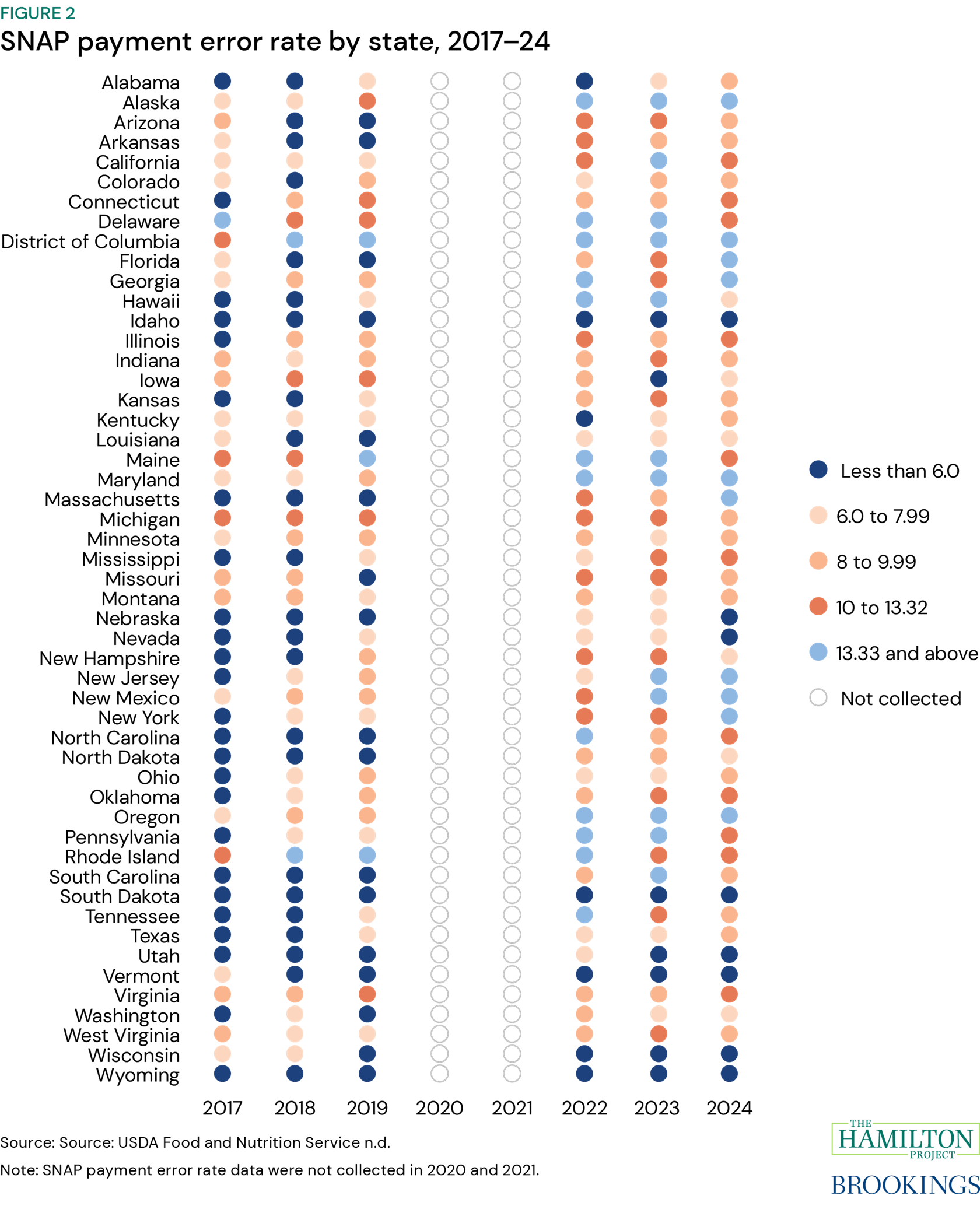

Figure 2 shows PERs by OBBBA bin (less than 6 percent; 6–7.99 percent; 8–9.99 percent; 10–13.32 percent; and 13.33 percent and above) since 2017. SNAP payment error rates fluctuate frequently across these arbitrary 2-percentage-point bins, which will make planning even more difficult for states. Forty-eight states and D.C. had PERs over that time period that fall into at least two bins: Thirteen states and D.C. had PERs in two different bins, 20 states in three different bins, 12 states in four different bins, and two states (Florida and Tennessee) in each of the five different bins. Post-pandemic, i.e. 2022–24, 11 states had a year with a PER of 6 percent or below, while 31 states and D.C. had an error rate above 10 percent at least once.

Only three states—Idaho, South Dakota, and Wyoming—have had PERs consistently below 6 percent since 2017. Eleven states have had an error rate below 6 percent in 2022, 2023, or 2024. Several states—California, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Tennessee—have, in the past three years, improved their PER from above 13.33 percent (full federal funding due to high error rate) to between 6.0 and 13.32 percent (state pays for a portion of benefits).

States will struggle to shoulder the rising cost of SNAP benefits during a recession

It is as yet unclear how each state will respond to OBBBA changes in SNAP policy as economic conditions, program enrollment, and payment error rates vacillate. Nearly every state is required to balance its budget each year. Under poor economic conditions, states tend to overestimate tax revenue; many states will struggle to shoulder the substantial costs of this policy change even under good economic conditions.

During a recession, total SNAP (as well as Medicaid) costs will increase as more families become eligible for the program due to declining income and/or job loss. Aggravating the pressures on states, SNAP error rates tend to increase during a recession when states must deal with an influx of new applicants and larger caseloads. At the same time, state revenues will decrease due to the recession, which makes it harder for states to add the staff needed to deal with these increased caseloads and to pay for an increase in the cost of program benefits. As a result, post-OBBBA, during recessions, both state payment levels and state payment rates (i.e., the share of benefits that states have to pay) will increase unless states make program cuts or end participation in SNAP. States literally do not have the flexibility or tools that the federal government has to borrow to cover increased program costs during a recession.

That states will have to pay more for SNAP during a recession due to a larger and more complicated caseload increases the likelihood that states will take damaging steps to cut SNAP or, if they choose to preserve SNAP, cut other parts of the budget. Since there is a three-year lag between a state’s payment error rate being reported and the consequences of that error rate on the share of benefits a state has to pay, if error rates increase during a recession, the increased cost share that will be triggered later will be a drag on state budgets during a recovery.

This OBBBA policy change will be damaging both macroeconomically and to state residents who need services and financial support. SNAP is a particularly efficient way to spend federal money to stabilize and stimulate the economy during a downturn. During downturns, SNAP benefits are spent quickly and increase spending at grocery stores. Consequently, SNAP benefits have a notably high multiplier: The economic benefit per dollar spent on SNAP during a recession is well in excess of a dollar (see box 1 for a review of the literature). Therefore, the consequences of restructuring SNAP to limit its capacity to expand during recessions will not be borne solely by SNAP participants but instead will impact the entire economy. With SNAP’s role as an automatic stabilizer hampered, there will be less stimulation of the economy, worsening and prolonging downturns.

Box 1. Stimulus effects of SNAP benefit increases during recessions

USDA has estimated that each additional dollar spent on SNAP benefits causes total economic activity to increase by $1.40 to $1.50 in a general economic downturn. There are no estimates of what would happen if SNAP benefits were instead cut during a recession, but the magnitudes are plausibly similar: more than a dollar in total economic activity lost for every benefit dollar cut.

The specific impact of increased SNAP benefits varies across recessions depending on the broader economic conditions. For example, during the Great Recession, the economic impact of SNAP increases was quite high, with a dollar of SNAP benefits causing between $1.74 and $1.79 in new economic activity. Included in this increase, for every $10,000 in new SNAP benefits in a county, one additional job was created in non-metro counties, and 0.4 jobs were created in metro counties. Later, in the COVID-19 recession, the American Rescue Plan’s SNAP benefit enhancement caused $1.61 in additional economic activity for every dollar spent.

OBBBA restructures SNAP into a program more similar to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which have had state matching requirements since inception. As every state participates, these programs can be considered automatic stabilizers; but, Medicaid and CHIP’s state cost sharing requirement do weaken them as automatic stabilizers, since states frequently make cuts to these programs when facing budget challenges, including during recessions. Indeed, in recent recessions, Congress has found it necessary to act to curtail the economic drag of state belt-tightening by temporarily increasing the federal share of Medicaid and CHIP expenditures to provide more financial resources to states.

During recessions, states often reduce spending on programs in their jurisdiction, like education, transportation, and public safety. States are not able to afford Unemployment Insurance expansions. A recent study found that when a state receives federal assistance that allows it to avoid $1.00 in program cuts, at least $1.70 in additional economic activity results. Indeed, the generalized problem—states are unable by themselves to adequately respond to recessions—is well-documented. Shifting SNAP costs onto states will exacerbate this problem. States that attempt to preserve SNAP benefits may find it necessary to make further cuts to state funding of education, health, or other programs as a result.

Meanwhile, state tax revenues decline along with the decrease in economic activity that characterizes a recession. While federal tax revenues decrease as well, the federal government can borrow to offset the gap that arises due to lower revenues alongside increased costs. In contrast, every state except Vermont is required to balance its budget each year and will be unable to borrow to meet the demands of its increased SNAP costs. In other words, states will now bear more of the cost of SNAP when they are least able to afford it.

A work-based safety net doesn’t work during a downturn

In an economic downturn, jobs are scarce, and more workers are unemployed and trying to find a job. Given the job losses and declining incomes that are symptomatic of a recession, more people become eligible for and gain access to social insurance programs like SNAP. Work requirements inhibit the countercyclicality of SNAP because they condition eligibility on both income and employment.

Time limit work requirements in SNAP require that participants successfully report that they spent at least 80 hours per month on allowable activities such as work or some types of job training. Time spent looking for work does not directly count as an allowable activity. If participants do not meet the work requirements or successfully document that they qualify for an exemption, then they are eligible to receive only three months of SNAP benefits in a three-year period unless they live in an area where work requirements are waived or for the months they are in compliance with the work requirement.

Rigorous research evidence finds that SNAP work requirements do not increase employment, as we describe more fully in this primer and these proposals. Further, expanded work requirements will diminish SNAP as an automatic stabilizer and will penalize workers during recessions, as discussed below.

What is the new OBBBA policy?

Prior to the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, so-called “able-bodied adults without dependents” (ABAWDs), then defined as people between the ages of 18 and 54 who do not have children in the home, do not have a work-limiting disability, and are not pregnant, veterans, people experiencing homelessness, or youth aged out of foster care, were subject to the time limit work requirements.

OBBBA newly exempts certain Native Americans who meet the definition under the Indian Health Care Improvement Act. OBBBA subjects far more SNAP participants to time limit work requirements, including:

- Non-disabled adults ages 55 through 64 without dependent children in their home.

- Non-disabled adults ages 18 through 64 whose youngest dependent child is between the ages of 14 and 17.

- Veterans, people experiencing homelessness, and those ages 18 through 24 who have aged out of foster care.

CBO estimates that OBBBA’s work-requirement-related provisions will reduce participation in SNAP by 2.4 million people in an average month over the next 10 years. CBO did not produce an estimate for the enrollment consequences to these policy changes when a recession hits.

Work requirements penalize workers

Eligibility for means-tested programs increases during an economic contraction because workers lose income or their jobs. These new participants worked in the past, and they will work again in the future; SNAP helps these families afford food as they look for work and start to work again. SNAP work requirement policy, however, does not engage with this dynamic at all, as it requires program participants to be working at least 80 hours a month in the very first month of benefit receipt or incur their first of three strikes. SNAP work requirements penalize those who recently lost their job, those who are looking for but cannot find work, and those who can only find part-time work.

USDA studied, and Elizabeth Cox, Chloe N. East, and Isabelle Pula summarized, the circumstances that precipitated SNAP enrollment during the Great Recession (figure 3). Conditional on observing a triggering event, this research finds that a full 91 percent of new SNAP recipients experienced a job loss (29 percent) or loss of income (62 percent) before applying for SNAP. Many low-wage workers are not eligible for Unemployment Insurance when they lose their jobs. Low-wage workers apply for and use SNAP as insurance to support them through this hardship. In fact, new evidence finds that simply receiving SNAP benefits improves employment outcomes.

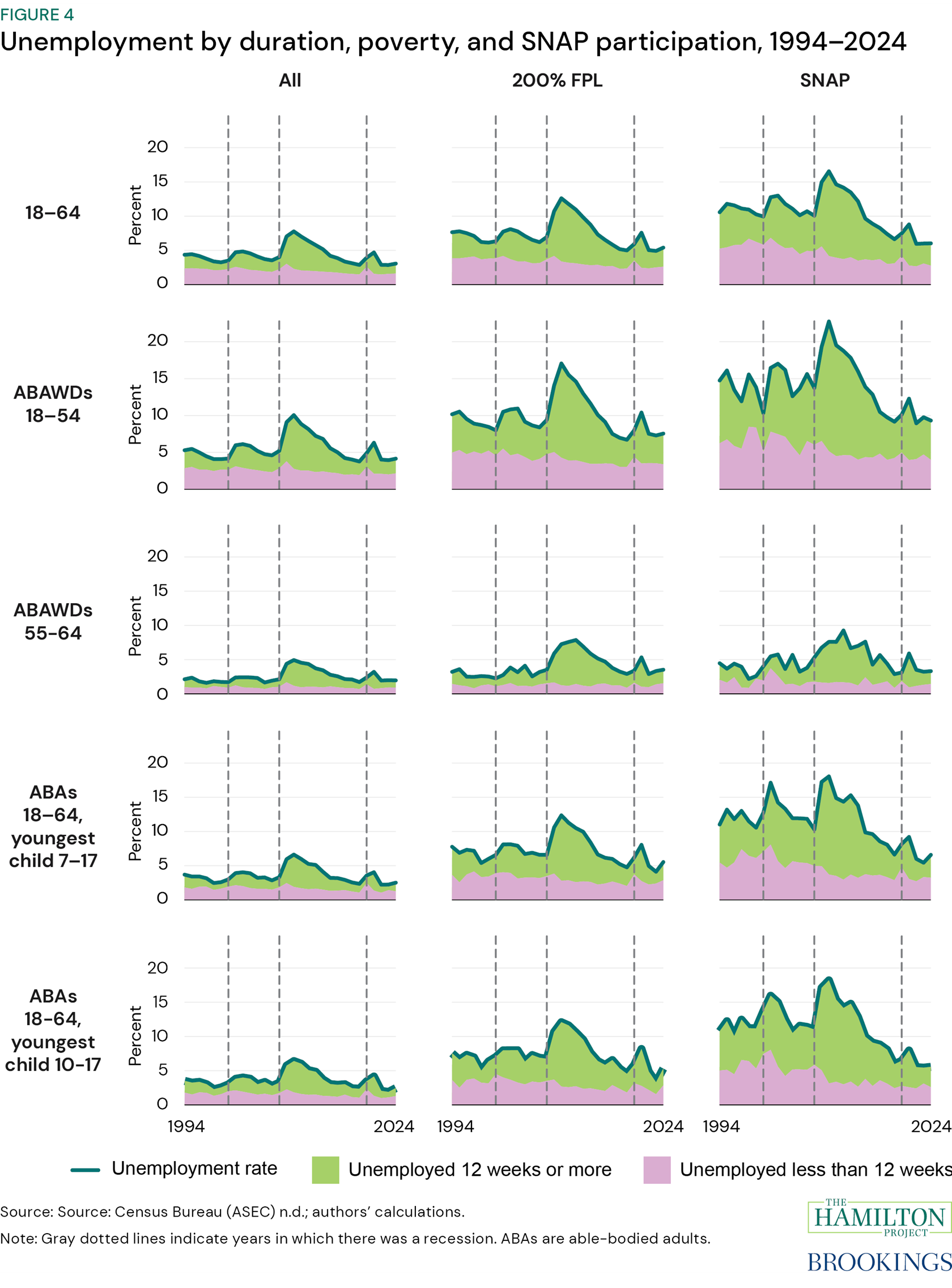

Figure 4 shows that unemployment is quite high among low-income and SNAP participating households and that unemployment durations in excess of three months (lime green) are pervasive among these groups, particularly during downturns and slow recoveries. For example, in 2010, the height of the Great Recession, the unemployment rate for able-bodied adults without dependents between the ages of 18 and 54 was 10.1 percent overall. For the same population under 200 percent of the federal poverty level, the unemployment rate was 17.1 percent, and for SNAP participants, the unemployment rate was 22.8 percent. Some 77.3 percent of SNAP participant ABAWDs who were unemployed were unemployed for more than 3 months. Had the OBBBA policy been in place during the Great Recession, not only would those unemployed SNAP participants have been dropped from the program, they would either have to come into compliance by meeting the work requirement in a given month or, if they could not find work, wait three years before becoming eligible again.

Figure 5 shows the share of SNAP participants who are in the labor force (the total at the right-hand side of the stacked bar) as well as the distribution of full-time work, part-time work, and unemployment (actively seeking work) in the survey month among SNAP participants who will be subject to the time limit work requirements under OBBBA. During recessions, the share of SNAP participants who are in the labor force increases, and the share of labor force participants who are unemployed also increases; participation in SNAP for these groups is countercyclical. Regardless of macroeconomic conditions, the majority of ABAWDs 18–54 and parents of older children are labor force participants. For those who are in this population and out of the labor force, work-limiting disability is quite prevalent.

In 2012, during the final phases of the Great Recession, about half of SNAP participants in each of the work requirement expansion populations who were in the labor force were looking for a job; for ABAWDs 18–54, two-thirds were in the labor force and looking for work. In the most recent year available (2023), a third of those with children 14–17, about 41 percent of ABAWDs 55–64, and more than half of ABAWDs 18–54 were on SNAP, in the labor force, and looking for work.

Work requirements thus penalize the unemployed, i.e. people who want to and are actively seeking work. Those subject to time limit work requirements have to show that they work or participate in otherwise sanctioned activity for at least 80 hours per month, but time spent searching for work does not count towards this requirement unless it is a supervised aspect of an employment and training (E&T) program or a participant meets the general work requirement through receiving Unemployment Insurance. In other words, if a SNAP participant is subject to the time limit work requirement, they will be removed from the program if they look for but cannot find work within three months and their state does not provide them a slot in an approved E&T program. States generally do not offer anywhere close to enough E&T slots during economic expansions, let alone during contractions.

Another reason that work requirements penalize working people is pervasive volatility in the low-wage labor market in terms of the number of hours worked per month. Elizabeth Ananat, Anna Gassman-Pines, and Olivia Howard find that even among low-wage service workers without minor children in the household who meet work requirements on an annual basis (i.e., who work an average of more than 80 hours per month over the year as a whole), 42 percent have at least one month with less than 80 work hours, and 25 percent have at least one month of unemployment. This was the case in 2022, when the economy was not in a recession and labor market conditions were improving.

The dynamics of the low-wage labor market—high levels of unemployment, high levels of long-term unemployment, and considerable hours volatility—is evident regardless of where one is in the business cycle. But, it worsens during an economic downturn. In recognition, during the past two recessions, Congress has suspended SNAP work requirements nationwide. Given this Congress’ and administration’s commitment to increasing work requirements across programs including SNAP, however, we are concerned that this necessary countercyclical policy will not be put into place when the next downturn comes.

Proposed SNAP work requirement waiver rules tie states’ hands

Up to now, states have been able to apply to USDA for waivers from SNAP’s time limit work requirements for local labor markets when economic conditions are weak and jobs consequently hard to find; waivers have been a safety valve for turning off time limits by place in such circumstances. By breaking the connection between SNAP eligibility and SNAP work requirements in places where local labor market conditions warranted, SNAP has been able to provide additional support to state and local economies that have had elevated unemployment or were experiencing idiosyncratic economic shocks even when the national economy was not itself weak.

As there is no one way to identify the economic conditions that make it difficult for workers to secure employment, the prior ABAWD work requirements rules included several measures of labor-market weakness (evidence of a “lack of sufficient jobs”) to determine whether a local or state area qualified for a waiver. Such measures included having a sustained elevated unemployment relative to the national average, defined as having an unemployment rate at least 20 percent higher than the national average over a recent 24-month period (commonly called the “20-percent rule”); high unemployment, defined as having a 12-month or three-month average unemployment rate above 10 percent; a statewide waiver rule for when the Extended Benefits component of the Unemployment Insurance program triggers on in a state; and a handful of other economic criteria that were less commonly used. Waivers can be requested for a wide variety of types of geographic areas, including states as a whole, smaller geographies like Indian Reservations, counties, cities or towns, and state-determined groupings of contiguous labor market areas.

What is the new OBBBA policy?

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act makes it nearly impossible to waive work requirements by place. It radically changes the waiver criteria: Only places with an unemployment rate above 10 percent (as a three-month average, 12-month average, or as yet undefined “An historical seasonal unemployment rate over 10 percent”) will be eligible for a waiver. Alaska and Hawaii can receive a waiver if their unemployment rate is 150 percent of the national average; these states may also temporarily exempt individuals from work requirements if they show a good faith effort toward implementation. OBBBA also only allows for place-based waivers to last for one year; during the Great Recession waivers could apply for up to three years.

In establishing work requirements in Medicaid nationally for the first time, OBBBA also introduces criteria in that program for waiving work requirements where labor market conditions are weak. Yet, those criteria differ entirely from both the old and new SNAP criteria. For Medicaid, states will be able to request a waiver from work requirements for a local area with an unemployment rate 8 percent or higher, for a local area with an unemployment rate 150 percent that national unemployment rate, or a place where the president has declared an emergency or natural disaster.

To be clear, SNAP’s 10 percent unemployment rule under OBBBA stands out as an exceptionally high standard. At the national level, 10 percent unemployment was reached in only one month during the entire Great Recession. About 40 percent of the population lived in a county where county-level unemployment never reached 10 percent for even a single month during the Great Recession, the deepest and longest recession in recent decades.

Work requirement waivers won’t kick in until it’s too late, if at all

Figure 6 shows how quickly different measures of labor market weakness responded to the Great Recession by county. It also shows the period during which Congress suspended work requirements nationwide (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act waiver) and the additional Unemployment Insurance-related waiver that the George W. Bush administration put in place (Emergency Unemployment Compensation). This analysis shows that the 20-percent rule has some procyclical characteristics, but this allows the rule to waive locations with relatively high unemployment early in a recession. During the depth of this recession, this analysis finds that tying waivers to the same rule that extends the duration of Unemployment Insurance benefits (EB) provided the most coverage. By contrasts, the 12-month and three-month 10 percent unemployment by county rules (blue)—the only criteria of these remaining under OBBBA—were both slow to respond to the onset of a downturn and failed to ever reach 40 percent of counties.

Limiting waivers to places with unemployment rates in excess of 10 percent (3-month average, 12-month average, or [as yet to be defined] seasonal average) undercuts recession responsiveness. Figure 7 shows how long it took counties to reach a 3-month average unemployment rate above 10 percent after the Great Recession started in December 2007.

Figure 7 and the accompanying state-by-state analysis show that limiting waivers to counties with a three-month average unemployment rate of 10 percent or above severely slows waiver availability even during a deep recession. During the Great Recession, 1,338 counties (128.9 million people) never reached a three-month average unemployment rate of 10 percent.

In the first three months of the Great Recession, which started in December 2007, only 122 counties (where 5.4 million people live) had a three-month average unemployment rate of 10 percent or higher. Within the first year, only an additional 126 counties (7.9 million people) hit a three-month average unemployment rate of 10 percent. Between the first and second years of the recession, 1,154 additional counties (126.4 million people) hit 10 percent unemployment with a 3-month average, an additional 338 counties (28.2 million people) between years two and three, 28 counties (1.8 million people) between years three and four. Between the fourth year and the end of the business cycle, 17 additional counties (1.0 million people) reached a three-month average unemployment rate of 10 percent or above.

Conclusion

Up until now, SNAP has provided much-needed relief to families when they fall on hard times. And, up until now, SNAP benefits have served as a crucial economic stimulus because when the economy turns down and more people lose jobs and income, more households have become eligible for the program and participants have quickly spent the benefits in their local economies.

Each of OBBBA’s policy changes to SNAP, however, weakens and undermines the program’s ability to alleviate hardship for families during downturns and diminishes SNAP’s vital contribution to stabilizing demand. Achieving sounder, more effective countercyclical SNAP policy thus will entail undoing the principal SNAP changes in OBBBA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aviva Aron-Dine, Katie Bergh, Stacy Dean, Chloe East, Bob Greenstein, Este Griffith, Farah Khan, Joseph Llobera, and Dottie Rosenbaum for gracious feedback. Tia Cole, Olivia Howard, Eileen Powell, Noadia Steinmetz-Silber, and especially Asha Patt provided superb research assistance. Joyce Chen and Jeanine Rees provided editorial assistance.