If the US social insurance system is an umbrella, the COVID-19 pandemic was a hurricane. To bolster the system, lawmakers came together to pass ambitious support packages, and even among lockdowns and soaring unemployment, poverty dropped to its lowest level in modern US history. The economic turmoil could have disastrously driven up poverty—but it didn’t.

Zach Parolin’s book Poverty in the Pandemic: Policy Lessons from COVID-19—highlighted at a September 2023 event co-hosted by The Hamilton Project—reinforces many of the policy lessons that The Hamilton Project identified throughout the pandemic, which are summarized below.

While some lessons are unique to the extraordinary circumstances spurred by the virus, much of what we learned about poverty—and policy’s power to reduce poverty—should be remembered and applied.

The pandemic’s toll on the most vulnerable

During the pandemic, Hamilton Project analyses illuminated how the economic fallout was exacerbating existing inequities. A survey of households revealed disparities in outcomes related to the COVID-19 pandemic across race/ethnicity and employment status. Black Americans were hit particularly hard by the pandemic’s public health and economic consequences. According to Bradley L. Hardy and Trevon D. Logan, Black Americans’ employment fell harder and was slower to recover, and the Black-white wealth gap left them with less of an economic buffer.

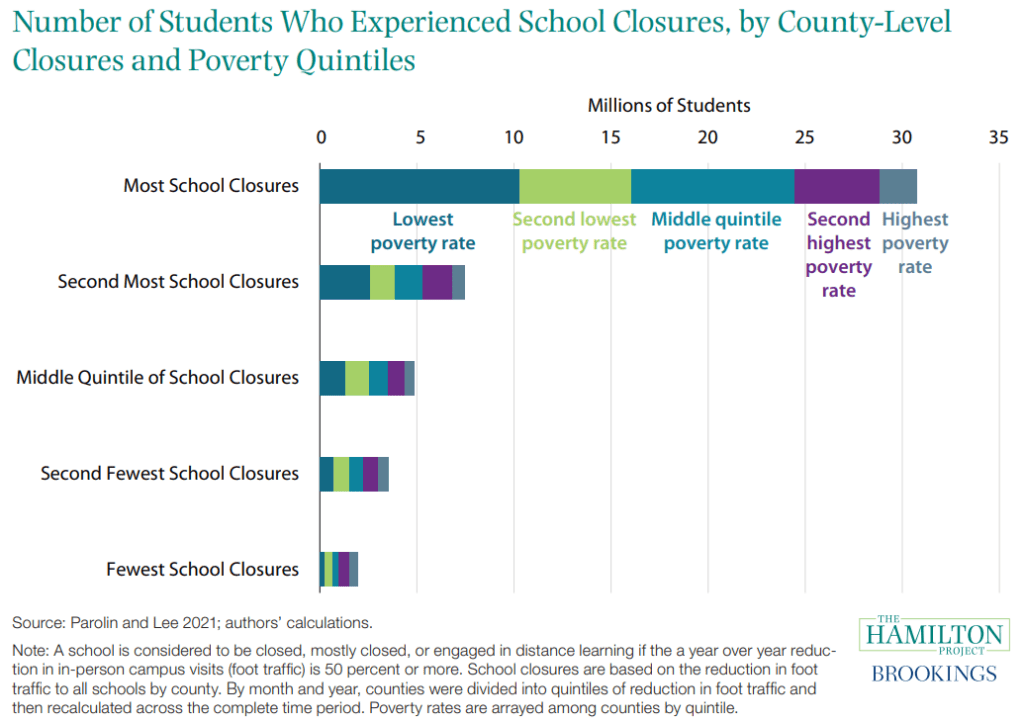

The pandemic’s disruption rippled through all workplaces, schools, and homes—but not equally. Essential workers, many of them low-income, were particularly exposed to the virus, and most lacked resources or representation to advocate for safer workplaces. Schools with fewer resources—disproportionately high-poverty schools—were typically less likely to provide an in-person learning experience (see figure below). Dual labor force participation particularly declined for less-educated couples with younger children, and caregiving stood out as an important factor. Lower-income families with children had higher and more volatile rates of food insufficiency.

Effective economic policy prevented an increase in poverty

The economic policy response was largely successful in protecting households from the pandemic’s immediate economic impacts, as detailed in Recession Remedies: Lessons Learned from the U.S. Economic Policy Response to COVID-19, a 2022 book from The Hamilton Project and the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at Brookings.

The two new policies in 2020 that had the most significant effects on poverty relative to the effectiveness of pre-pandemic policies were the expansion of Unemployment Insurance (UI) and the Economic Impact Payments (EIPs). Support through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC), as well as the strong labor market recovery, also helped to lift households out of poverty in the midst of the pandemic.

UI expansions, the Recession Remedies chapter finds, offset income losses and delivered the most benefit to lower-income workers. EIPs served as an efficient and quick source of support for households, though the Recession Remedies chapter flags that households in the lowest income group were less likely to have received an EIP on time or at all.

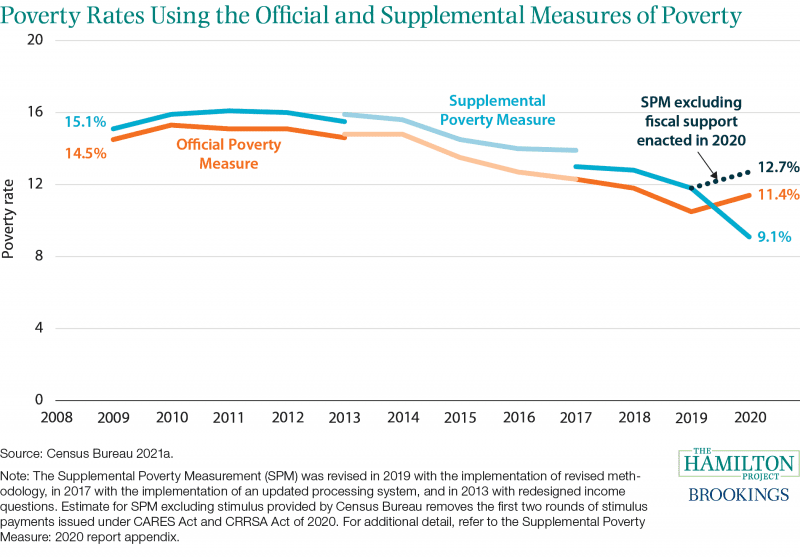

If Congress had not enacted relief for families, estimates predict that the Supplemental Poverty Measure would have risen to 12.7 percent. Instead, it fell to 9.1 percent (see figure below). For some demographic groups, the reductions were even larger.

Pandemic policies particularly reduced poverty among children. The Recession Remedies chapter on child well-being finds that the most important factors that kept children out of poverty in 2020 were, in order: the EIPs, refundable tax credits (the Earned Income Tax Credit and CTC), UI, and SNAP. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and WIC played small roles.

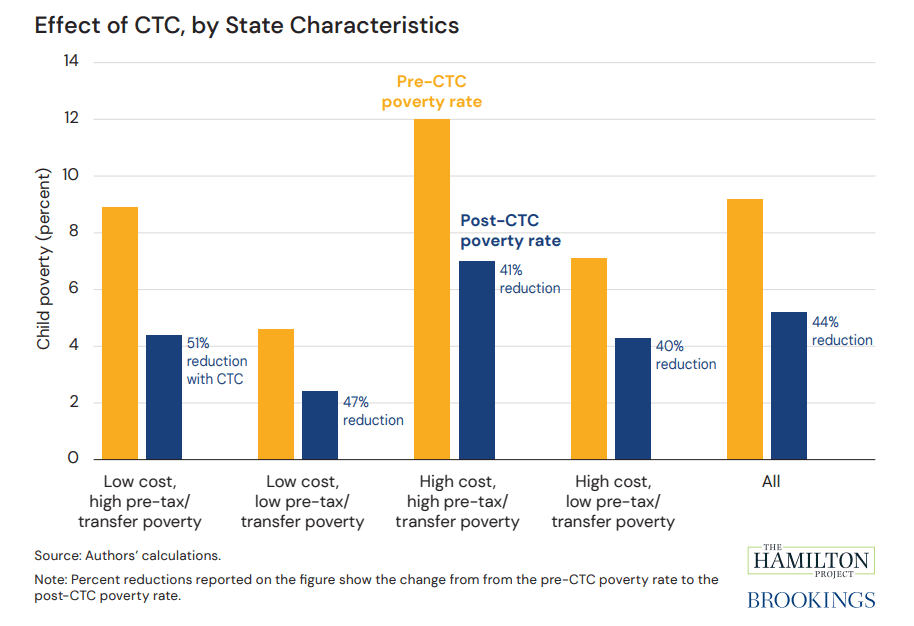

The American Rescue Plan greatly expanded the CTC for tax year 2021, reducing child poverty by 30 percent or more. The historic poverty reductions were the highest in low-cost, high poverty states (see figure below).

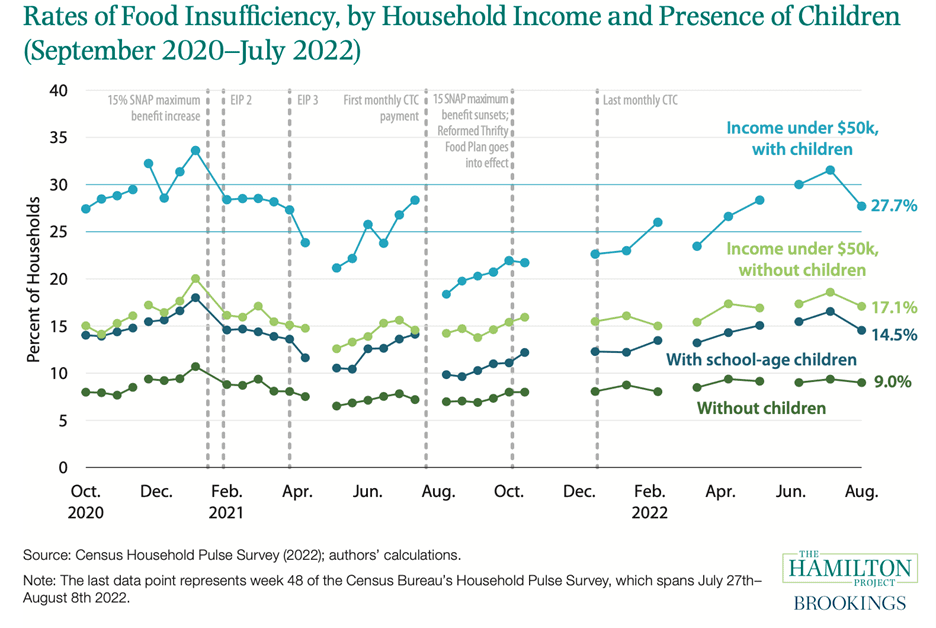

Policies that expanded household resources also coincided with a reduction in food insufficiency, particularly for lower-income families with children (see below figure). In tandem with new flexibilities and programs like the Pandemic EBT program, food insecurity held steady from 2019 to 2021 at a time when increasing rates of food insecurity would be predicted.

Beyond the effects of the anti-poverty programs listed above, a new program, Pandemic EBT, which provided resources to purchase food to family’s whose children lost access to school meals, reduced food insufficiency. This program was reformed throughout the pandemic to cover time gaps where no prepared meals were consistently provided, including summer months when school is out of session. In December 2022, Summer EBT was authorized as a permanent program. In addition to their evaluations of Pandemic EBT throughout the COVID era, THP’s Lauren Bauer, Krista Ruffini, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach made the case for in-kind benefits like Pandemic EBT and Summer EBT as an effective strategy for reducing food insecurity.

Lessons for post-pandemic poverty prevention

While the pandemic demonstrated the power of policies to protect people from economic downturns, it also highlighted areas to be fixed or improved.

The Hamilton Project has released policy proposals aimed at more effectively dealing with economic downturns. Some of these policy proposals offer ways to improve the social insurance system by reforming UI partly through making it a fully federal program, targeting aid to the neediest families by strengthening TANF, strengthening the housing safety net through automatic stabilizers, filling gaps in the child nutrition patchwork with in-kind nutrition assistance, making work pay better through the Earned Income Tax Credit, enhancing the Child Tax Credit to reach the most vulnerable children, and more.

One overarching recommendation is emphasized by both Recession Remedies and Parolin’s book: automatic stabilizers. With automatic stabilizers, economic indicators can trigger tax and spending changes without policymaker action. “To prepare for the next crisis, Congress should learn its lesson from the pandemic (and the Great Recession): reduce the crisis-era pressure on policymakers as they seek to balance the timeliness, targeting, and duration of income supports by implementing income support benefits that are triggered as soon as an economic downturn begins” Parolin writes (209), referencing policy recommendations from “Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy,” a 2019 book by The Hamilton Project and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. By making effective policies in a downturn more automatic, the concern would be lessened that policymakers would fail to act quickly and sufficiently in an economic crisis. That would improve economic outcomes even in normal times as well.

Automatic stabilizers can also help to better target fiscal policy to those who need it most. A total of $5 trillion was spent responding to the COVID-19 crisis. “The good news is that many of the most important benefits could have been achieved at much lower cost,” Wendy Edelberg, Jason Furman, and Timothy F. Geithner write in their Recession Remedies chapter. “Outside of a recession, the amount of additional income necessary to pull all households out of poverty is about $175 billion.”

Outside of a pandemic, the political calculations around expanding social insurance are of course different. But, the effectiveness of the policies implemented during COVID-19 can serve as reminder that poverty is a policy choice. As Parolin concludes:

“In short, we witnessed the menacing consequences of poverty but also the enormous power and capability of the state to reduce poverty and improve well-being among households going through difficult times. We owe it to all those who happen to experience life in low-income America to apply the lessons learned during the pandemic as we move forward” (216).