Data

THP visualizes economic issues through figures and data interactives.

Interactive

Office-to-apartment conversion calculator

A calculator can determine the financial viability of office-to-apartment conversions and quantify the amount of subsidies needed.

Read More

Explore All Data

Interactive

Office-to-apartment conversion calculator

A calculator can determine the financial viability of office-to-apartment conversions and quantify the amount of subsidies needed.

Interactive

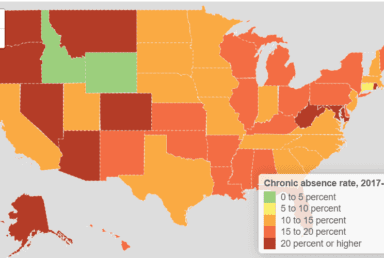

Chronic Absence across the United States, 2017-18 School Year

In 2021, The Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution has re-published an interactive map using national chronic absence data reported by school districts…

Interactive

Career Earnings by College Major

See the accompanying economic analysis, "Major Decisions: What Graduates Earn Over Their Lifetimes." Over the entire working life, the typical college gra…

Interactive

Who Stands to Lose If the Final SNAP Work Requirements Rule Takes Effect?

Click here to view the full interactive. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has released a final rule that would limit eligibility for SNAP work requireme…

Interactive

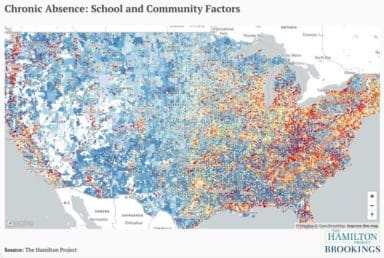

What are the Factors that Affect Learning at Your School?

Visit the interactive map, Chronic Absence: School and Community Factors. Reducing chronic absence and developing conditions for learning are instrumental…